For 45 Winters, Colorado's Reluctant Climate Scientist Has Been Quietly at Work

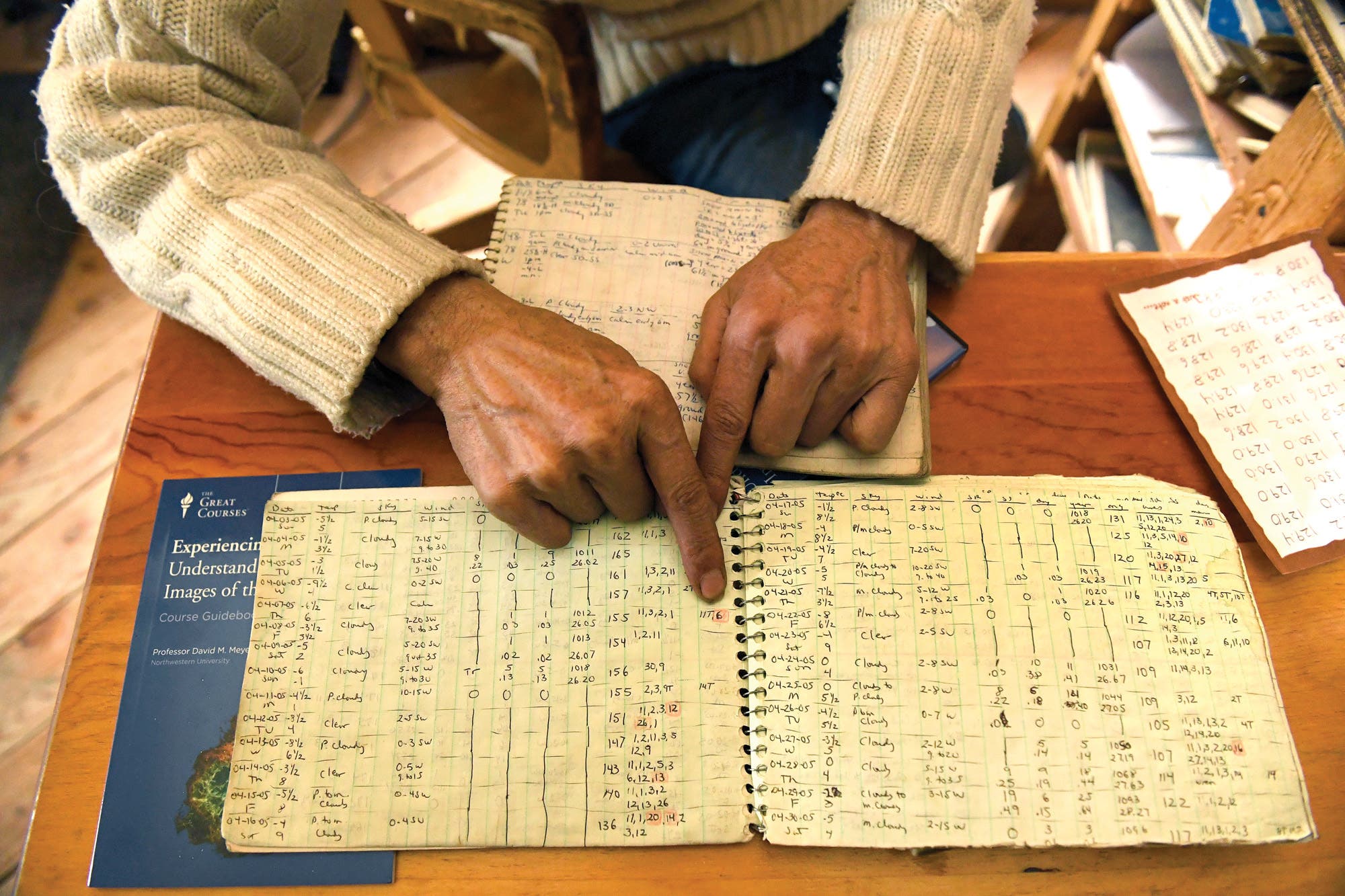

(Photo: Morgan Heim)

billy barr finds his reputation as a hermit amusing—misleading, but amusing. Sure, the 68-year-old mountain man who spells his name with all-lowercase letters has lived in the ghost town of Gothic, Colo., for 47 years. Sure, his social interactions over the years have been limited, but that’s a result of his environment more than want or desire.

“I like having people around. I keep lobbying the Lab to have three sets of caretakers instead of just two. I’m a social person, I just live out here,” says barr. “In the summer I don’t shut up because I hardly talk to anyone all winter.”

The lab barr refers to is the Rocky Mountain Biological Laboratory, where barr is employed part-time as the accountant. Founded in 1928, RMBL is the heart pumping life back into Gothic after the town was abandoned by its mining inhabitants during the silver and coal mining busts of the early 1900s.

Every summer, the Lab draws one of the largest annual migrations of field biologists and students, all flocking to Gothic to study its rich and diverse ecosystems.

But come winter, when snow blankets the valley and plows stop tending to the gravel road that connects Gothic to the nearest town—Mount Crested Butte, 4.5 miles away—only barr and a handful of students-turned-caretakers remain. And that’s when barr retreats to his solitary routine of watching snow fall from the sky.

For 45 winters, barr has kept himself busy in Gothic by recording the weather—daily high and low temperatures, snow accumulation, and snow density—twice a day, every day, all winter long.

barr first came to Gothic in the summer of ’72 as part of a group of environmental science majors from Rutgers University. “Over the course of that summer I had to analyze what was in the water to see how it changes with decreasing water levels and increased recreational use. I hardly remember honestly, I haven’t done science since then,” barr says.

Except, of course, he has. Before climate change and global warming were on most peoples’ radar, barr had already amassed decades’ worth of valuable weather data.

Since barr shared his treasure trove of data with a scientist at RMBL a few years ago, climate scientists from far and wide have come knocking on his door. And barr, dubbed “the Snow Guardian,” happily shares his records—he doesn’t really do anything with them, anyway. “I have opinions about what I’m seeing, but I don’t use them. I leave that to the people who use my data.”

So, with no agenda, no skin in the game, barr observes, winter after winter, how his immediate environment is changing.

“One thing that’s obvious is that half the record lows are from the first 10 years I was here… If you’re doing 45 years of records, that means it should have only been 20 percent.”

Just one of barr’s objective observations. Ask him how he feels about the warming trends, and he doesn’t couch his answer in positive or negative terms. Rather, he explains how it affects him on a personal level.

“I’m not crazy about big heavy winters. I’m 68 now. Shoveling that dense snow—that’s how my back went out last winter. But on the other hand, my water froze the day after Thanksgiving because we had no ground cover. When we get snow in November, which we always do, it warms up and melts away, so there isn’t enough ground cover to insulate my waterline. So, ironically, the warming trend has caused my water line to freeze four times in the last nine years.”

When his water line freezes at the start of winter, barr has no choice but to haul water from RMBL to the cabin he built on his own property half a mile away. Because he doesn’t own a car, and roads between his house and RMBL don’t exist anyway, barr skis the half mile to RMBL twice daily.

During the winter, skiing is barr’s only way to get around the beautiful yet rugged Gothic valley. When he needs to replenish groceries, he skis four miles along Gothic Road to reach the nearest bus stop at the Snodgrass trailhead, catches the bus to the Crested Butte ski area, then either takes a bus into Crested Butte (4 miles away) or to Gunnison (31 miles away).

Though life can be solitary and challenging during Gothic winters, especially as he ages, barr has no plans of leaving. Over the span of nearly a half-century, he’s found a routine that keeps him busy enough to survive the long winters.

“I say that as a joke, but also seriously. It was so bad growing up as a male in the ’50s and ’60s in a culture I did not fit into, constantly hit with media telling you to be a certain way. Being out here on my own the first years was just a relief and enjoyable.”

In recent years, barr hasn’t been so alone in Gothic. Aside from the students and scientists who come to study at RMBL in the summer, barr now also sees thousands of recreationalists coming to Gothic to explore the Elk Mountains on motorcycles, ATVs, snowmobiles, mountain bikes, and backcountry skis.

“Recreation is becoming more popular, which is a good thing. Sure, I’ve had problems with the summer tourism. Before my fence was up, people were driving through my yard. But hey, in the winter, at my age, if someone wants to break trail for me—come on out!”

Originally published in the October 2019 issue of SKI Magazine.