Warren's World: The Cheapskate Brothers

Originally published in the March/April 2002 issue of SKI Magazine.

I first met Klaus Obermeyer in the fall of 1948 in Sun Valley, Idaho. He had sailed and then hitchhiked there from Germany with the clothes on his back, $12 in his pocket, a pair of lederhosen and no fear of hard work. When I was introduced to Klaus, he happened to be nine feet down in a hole that he was digging for a septic tank with our mutual friend, “Flush” the plumber.

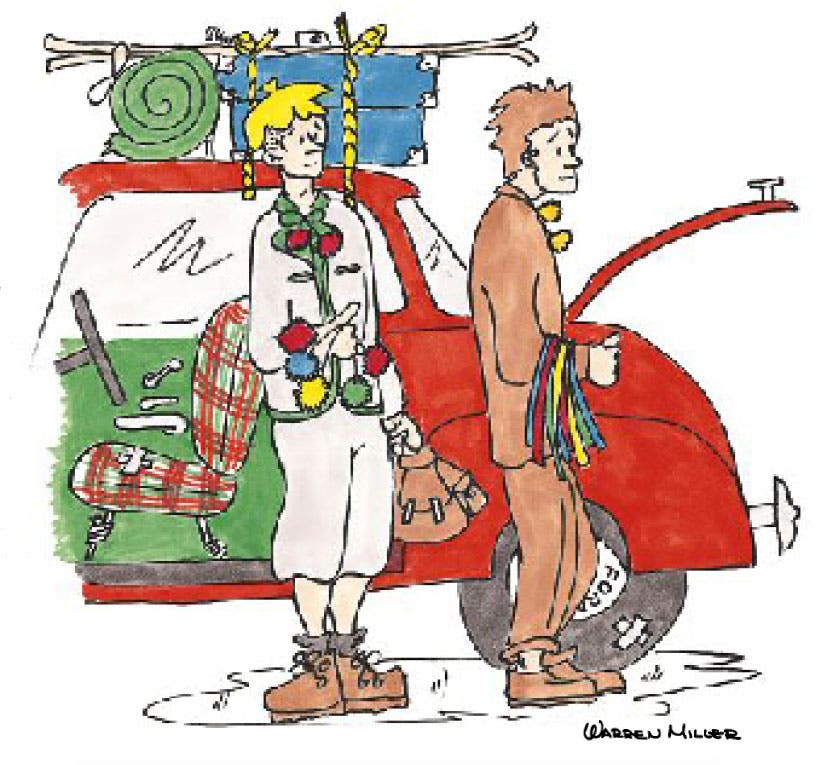

When the hole was finished and we were taking a break at Flush’s cabin, I learned that Klaus had hired Mrs. Flush to hand-make his genuine, “imported” Bavarian Koogie ties. They looked like the pompoms that high-school cheerleaders once wore on their saddle shoes. They had just enough yarn so you could wrap them around your neck, tie a bow and wear them instead of a necktie. Klaus claimed Koogies were the latest fashion rage in the Bavarian Alps (where fashions apparently change slowly), and he had already cornered the local Ketchum market.

By the time we finished our third cup of tea, I’d also hired the talented Mrs. Flush to dye my Army Surplus nylon-parachute-shroud-ski-boot-laces. At the time, boot laces were made of cotton and would begin to tear after only a week on the slopes. I already had 600 orders for my revolutionary “guaranteed-for-the-life-of-your-ski-boots” laces from all seven ski shops in Sun Valley, Ketchum and Hailey. And I already had three people standing by to burn the ends of the nylon laces for two cents a pair. Mrs. Flush would then dye them various colors for a penny a pair.

The Army Surplus parachute shroud material cost me about two cents a pair, and manufacturing was running five cents a pair. I was wholesaling the laces for 25 cents a pair, which I thought was a healthy margin. Klaus, on the other hand, was aiming for the big time: He was charging a dollar and a half, wholesale, for his Koogie ties.

Later, while sitting in front of Flush’s fireplace, Klaus and I decided to go on a Koogie-tie, ski-boot-lace sales trip together. I owned a high-mileage Ford coupe that I had remodeled so I could sleep in the back of it on my summer surfing trips. It could uncomfortably sleep three people, if one of them was short enough to sleep in the front seat so the other two could sleep in the double bed in back.

Klaus and I started out on our grand adventure. We loaded the car with a Coleman cooking stove, a jug of drinking water, a wooden box with five frozen rabbits, six frozen trout, two pounds of elk meat, a couple of pounds of venison and some peanut butter. We also had a box full of cooking utensils, a road map, two sleeping bags, a couple of pillows and nine gross of my revolutionary ski boot laces. Klaus brought a cardboard suitcase full of genuine Imported Bavarian Koogie ties and a change of clothes.

I also had my genuine Rit Dye color chart so the ski shops could pick the colors they wanted. (A 25-cent package of Rit dye would color 144 pairs of shoelaces.)

It took two days of traveling and selling to refine our cheapskate travel routine. I had learned that the best and safest place to sleep in the car was in church parking lots or near a police station. If the car faced east when parked for the night, the morning sun could shine in the windshield and warm the interior. Then we could climb out of bed without getting frostbite from any of the metal parts inside the car.

By the time Klaus and I had visited half a dozen ski shops and sporting goods stores in Boise, he was almost out of his Koogie ties and I was already out of shoelaces except for a set of assorted color samples. We sold at every store we visited: No exceptions. By the end of the trip, I had orders for 4,000 pairs of laces. Our business was so good that we eventually tried to spend a night in a motel. However, when we found out that it cost $5 a night, it was clear that a motel was out of our financial reach.

After sleeping in the car, we looked like a pair of street people who had spent the last three weeks living under an overpass. But we deevised a simple plan to clean up for our morning ski-shop sales calls.

At that time, Klaus’ English wasn’t very good. But he was charming, so he would approach a maid who was cleaning motel rooms early in the morning. He would offer her 50 cents if she would give us a couple of towels and let us use the shower in one of the motel rooms before she cleaned it. He was so good at telling his story about escaping the ravages of World War II that occasionally a motel maid even gave him back the 50 cents so we could buy breakfast or a couple of gallons of gasoline. Back then, a stack of pancakes cost 25 cents and gasoline was 23 cents a gallon.

The saga of the Cheapskate Brothers, Klaus and Warren, covered the entire western United States and spread the gospel of imported Bavarian Koogie ties and Army Surplus nylon-parachute-shroud-ski-boot-laces. We hit Boise, Twin Falls, Yakima, Pendelton, Walla Walla, Seattle and then traveled down the coast to Portland, San Francisco and Los Angeles, where Klaus really scored big with orders. To celebrate our growing bank accounts, we stopped in a Swiss restaurant. After Klaus finished yodeling, the owner bought Koogie ties for his entire wait staff and picked up the tab for our Wiener schnitzel and strudel mit schlog.

The most important lesson we learned is that we would have to work all of our lives to be an overnight success. Today, Klaus Obermeyer heads a ski apparel company that sells about $30 million worth of clothing a year. I still don’t know what I’m going to do when I grow up.