Avoiding the Knife

This past winter I lived the skier’s worst nightmare. Though I didn’t hear or feel a pop in my knee, I sensed it the second it happened. The accident was nothing epic. I wasn’t cliff jumping or racing gates. But it didn’t matter. My ski season was over.

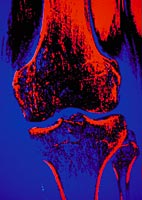

Tearing an ACL is serious business. The ACL¿anterior cruciate ligament¿is the most prominent ligament in the knee, connecting the femur and the tibia. It acts as a rope, holding these important bones together and stabilizing the knee while allowing it to move, extend and twist safely. When the ACL stretches too far, especially in a wrenching motion, it tears. Women are at greater risk for this injury because they have weaker hamstrings (which support the knee) and even because of changes in their menstrual cycle.

The ACL can tear partially or fully, and, at first glance, the severity that determines whether or not to have surgery is gray at best. Some doctors recommend surgery regardless of the degree of damage; others believe that only a full tear warrants going under the knife. Some athletes completely do without a functioning ACL. Denver Broncos quarterback John Elway tore the ACL in his left knee, chose to not have it repaired and won two Super Bowls.

Elway is a rare case. Most people with full ACL tears end up in the operating room. “Ninety percent of my knee patients have complete tears and require surgery,” says Dr. Joanne Halbrecht, an othopedist specializing in sports medicine in Boulder, Colo. “Someone like Elway is a tighter-jointed person, not as ligamentally lax, with very strong quadriceps and hamstrings.” It all comes down to stability. If your knee buckles or gives out, you likely need surgery. If it doesn’t, you’ll probably be able to recover with an intensive round of physical therapy. Doctors assess stability with a quick manual test called the “pivot shift.” If your knee “jumps” as the doctor manipulates it, it is unstable; if it doesn’t jump, it’s solid and secure.

I wish I had known some of this when I went down. The first doctor I visited took a quick look at my knee, told me I needed surgery and recommended I get an MRI “just to be sure.” Questions like “should I ice it” and “should I walk on it” were answered with “if you want,” and all lines of conversation led to one solution: surgery. I was sent on my way in about 5 minutes, and though my knee was throbbing and my head was spinning, I knew I hadn’t been given the whole story.

I was prepared for surgery. But considering I’d lived a healthy life up until that moment, I needed to at least know I was being heard in order to comfortably make that step. I went for the MRI and began a research process for a new doctor that left me with all sorts of recommendations that seemed difficult to sort out. Fortunately I have a doctor in my family, and he gave me one key piece of advice: “Before making an appointment with a doctor, get him on the phone. Call and leave a message. If he doesn’t call back, don’t see him.”

That helped me find my second-opinion doctor, who reviewed my MRI and assessed that although about 40 percent of my ACL was indeed torn, my overall stability was too good to warrant surgery¿I had passed the pivot test. “You don’t just want to jump in and operate,” she says. “There’s no condition that cannot be made worse with the wrong surgical procedure. It doesn’t hurt to have a trial of physical therapy with a partial tear.” Which is just what I did. I was banished to intensive therapy, where I’ve been working out harder than I ever thought possible.

Now, 4 1/2 months out, I’m doing the low-impact thing¿swimming, biking, in-line skating¿and my knee has never given out. Though I participate in these activities in short bursts and have to ice down each time, I’m on the road to recovery. A recent test determined that the strength of my injured leg is between 75 percent and 90 percent of the good one¿a point that many post-op ACL patients take betwween 6 and 8 months to reach.

My doctor believes that one day I will be able to run and ski again, but she doesn’t say when. There’s nothing definitive about this process¿it’s very much a day-by-day thing. All I know for sure is that I need to keep strengthening my knee.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m not anti-surgery. But if it ever comes to this for you, get a second opinion. It might save you a lot of unnecessary discomfort. As for me, I’ll see you out on the hill sometime very soon.

Health Hit

Standard ACL surgery costs about $3,000 plus about $7,000 in hospital fees. It is covered by most major insurance policies.