This is How You Get Extreme In Taos, N.M.

A female competitor charges down Oster. (Photo: Keri Bascetta)

“Jill, this is absolutely nothing like a JV soccer game,” I say slowly and deliberately to my friend and former coworker, who’s standing comfortably in ski boots far too close to a cliff on Taos Ski Valley’s West Basin.

We’re with other athletes waiting for our turn to compete in Taos’ Freeride World Qualifier, one of many nationwide extreme skiing competitions that serve as feeder events for the professional-level Freeride World Tour.

Jill, who is young enough to be my daughter, convinced me to enter this event in Taos by comparing it to kicking a ball around on a grassy field.

Related: 5 Wild Ski Adventures to Make Your Stomach Drop

“Oh, come on, this is amateur hour,” she says, casually leaning forward on her poles, her bib slipping down her willowy arm. “That girl looks like she’s only been skiing for two years. You got this.”

I watch the other competitor carefully pick her way down the cornice, cliffs, rocks, and vertical pitch of set-up concrete from my safe seat in the snow, kicking in my heels and trying not to think about the crowd below.

A more apt comparison than soccer, I think, might be walking out of my first seventh-grade dance at a new school with my dress ripped up the butt from bending over in the bathroom. Except this time, instead of everyone being able to see my control-top pantyhose without any underwear, they can watch me lacerate my spleen.

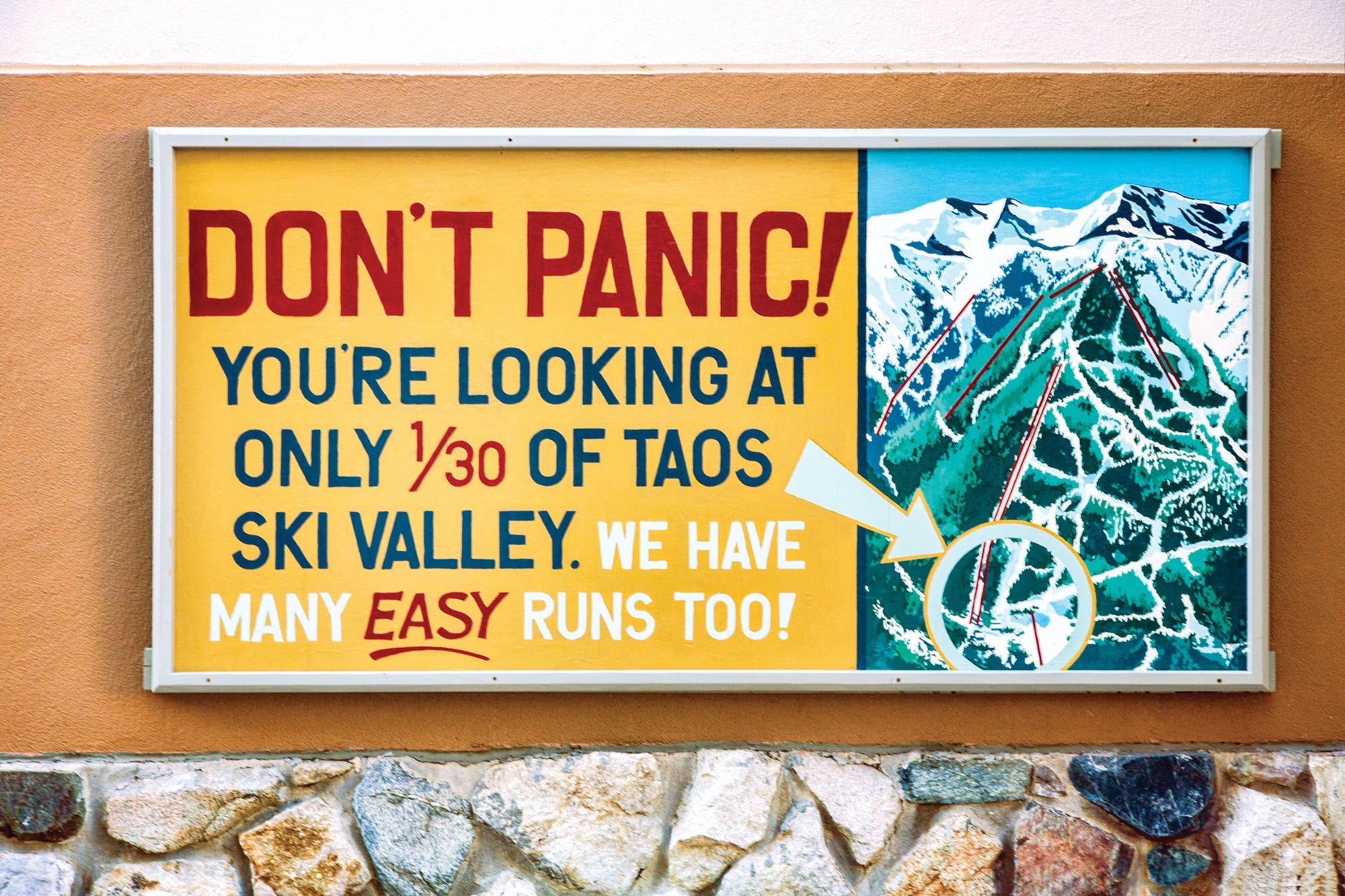

“Oh my god, Beekman, I’ve never seen you like this! You need to channel yourself! Just watch the other girls. They’ll inspire you,” she says, pointing past a sign that broadcasts the most unhelpful warning in signdom—“Unmarked Obstacles Exist”—to another competitor cautiously dropping in.

She’s right. I am usually not like this. Up until now, my “fake it until I make it” strategy has worked (though my 12-year-old daughter would refute, “Mom, we don’t even own an X-Box”). I myself taught Jill in countless client calls that as long as you’re sure of yourself, it doesn’t matter if you actually know what you’re talking about.

Related: These Resorts Have Risen in the SKI Mag Rankings For The Last 5 Years—Can They Keep it Up?

Now, however, standing atop this godforsaken pile of jagged rocks that are waiting to tear my legs from their cozy hip sockets, I have reverted to my awkward seventh-grade self, shuffling through the crowd sideways in too-big flats. In this moment, the only thing I am sure about is that I should never have let her talk me into this.

"I, meanwhile, was busy telepathically pleading with the kids standing on top of impossible cliffs to think about their mothers."

Yesterday, we drove up the winding two-lane road through the charmingly ramshackle town of Arroyo Secco to the little snowy pocket of Taos Ski Valley. Rounding the last bend, I caught my first sight of Al’s Run, towering straight up, with huge moguls stacked like oranges in a fruit cart.

The steep road ended abruptly, and the sidewalk skirted a stream that gurgled underneath the wooden walkway and the Stray Dog bar, outside of which lounged a few of its friendly namesakes.

We pulled up at the Blake Hotel, a charming gem that somehow pulls off being both luxurious and relaxed. In fact, Taos Ski Valley as a whole was even cooler than I expected—a purist’s resort. Funky, quaint, unapologetically steep, with one place to buy beer and Cheetos and zero places to buy a purse. It’s like a mixture of Bavaria, Mexico, and funky little Nederland, Colo., and I felt right at home.

We booted up and practiced our Spanish with Diego from Peru, a ski valet attendant who would remember our room number and have our warm boots ready each day thereafter. He smoothed a strip of duct tape on our skis to write our names on them, and Jill took the Sharpie and scrawled her nickname, “Lil’ Kim.” He looked at her—6 feet tall, blonde, and gorgeous—and at me—5 feet 4 and in desperate need of a highlight—and laughed, way

too hard.

We walked the 30 or so steps to the lift in the sun-baked plaza. The smell of woodsmoke hung in the air, and the golden light warmed our faces. “Have fun out there, ladies!” said a young local bro, tossing his carefully mussed mullet at Jill. “Thanks!” she waved and smiles. Fun, I grumbled to myself, would be slush bumps, bad ’80s music, and beers on the deck of the Bavarian.

We skated through empty lift mazes and scouted lines on West Basin all afternoon, where the comp would be held. Jill competed here in the same FWQ a couple years ago (she founded the University of Denver’s Freeride Team), so she skied from drop to drop, inspecting landings.

I, meanwhile, was busy telepathically pleading with the kids standing on top of impossible cliffs to think about their mothers, and marveling that, evidenced by the near-vertical sea of sharks, snow doesn’t stick to slopes this steep.

The sound of my skis skitching cautiously through them was a combination of squeaks, groans, and rasps that reminded me of my first rap tape, EZ-Duz-It, which came out when I was 13.

“What do you think about this one?” Jill said, her skis fully flexed standing in a narrow chute above a sharp cliff. “Uhhhhh….” I replied, as roller balls from skiers above me tinged down the slope and tagged me in the thighs. “Well, the takeoff puts you landing right into another cliff. If you turn in the air, you land in a bomb hole.”

The snow was so firm it sounded like a hollow door when I whacked it with my pole.

“This could be the hit. I’m just gonna try it,” she said, taking a deep breath, her loose hair strands waving in the wind. I backed up and leaned on my poles, one of which broke sickeningly through the crust into a pile of rocks hidden beneath. My body felt like it was stiffening into rigor mortis, and I hoped she couldn’t see my leg shaking.

“You got this, Jilly!” I called weakly.

She hiked up a few more feet and then pointed ’em, clearing the bomb hole by about three feet. It was not clear at first whether or not she landed it, owing to the huge spray from her edges, but then she emerged near the bottom rocketing down head-first on her stomach with one ski on.

A few friendly moguls in the run-out caught her like a catcher’s mitt. “I’m OK!” she waved cheerfully with her pole.

My strategy, on the other hand, was to keep my skis on the ground, which Jill strongly felt was unacceptable. “Come on, you want to push yourself hard enough to where you might mess up. That’s what this is all about,” she said as I handed her other ski to her and shook snow out of her hood.

I assured her I did not need to get air to mess this up—that would undoubtedly happen organically.

Then, on the final warm-up run, she pointed out a little hop between two trees that would become the equivalent of Chekhov’s famous shotgun.

We looked at it from underneath, and it had no visible rocks around it or under it, so it seemed doable, even by me. But I didn’t know what it looked like from above, and if there was anything these scouting runs have taught me is that everything looks so, so much scarier from above.

Related: How Steep Is Steep? Explanation of Slope Angle.

“OK fine.” I unwisely conceded. “I will jump off the little bump through the trees.”

The morning of the comp began in chaos. This is not unusual for either of us, and it’s absolutely expected when we’re together. From the time we arrived, we have been a total shitshow. “Are we late? Did we miss it? Where is it? Do you have a room key? Is that the one that works? Have you seen my wallet? Have you seen my phone? Does my binding look wiggly?”

Apparently, there is such a thing as “Taos time,” but even here, we lag behind. We were not registered yet, nor did we know where said registration takes place. I was counting on Jill, who’s done this before and who has the social media savvy to know there was a Facebook page with every bit of information we could ever have needed on it, and she was counting on me as the wizened elder to have divined the time and place through sheer life

experience.

Needless to say, when I ran into the photographer in the hotel elevator, still in my PJs, I quickly realized we were already late, and that the final dram of whiskey last night should not have been part of our training regimen.

“Jill, we have to be on the lift in 15 minutes. And registered before that,” I hyperventilate as I burst into the room.

“OK, we got this,” she says, perennially calm.

We charge out the door, Jill looking totally put together and me looking like a homeless person who just scored a ski-clothes donation. I don’t know how to put on my new POC back protector, mandatory for the comp, so I throw it over my shoulder and silently vow to never, ever engage in another sport that requires a back protector.

We clomp into the lodge and walk to the registration desk, where I overhear my old friend Tom Winter, manager of the Freeride World Tour, asking our photographer (hired to document this debacle for SKI), “Where is our ‘athlete?’” making air quotes around “athlete.”

“I’m right here,” I retort, waving my middle finger.

“You got backflips in your bag, Beekman?” he teases, earning another middle finger.

We sign all the papers, hand in our copies of health insurance cards (“Don’t think about the deductible” becomes my new mantra), and choke down a breakfast sandwich that tastes as though it had been sitting in the warmer all night.

We take the early lift up and when we get to the top, the athletes bootpacking up the West Basin in shiny helmets and colorful outfits look like a line of action figures marching into battle.

We hike up behind them, then duck under the closed for competition rope at the top, where a ski patroller sits clipping his fingernails in the morning sun. I throw my skis down in the snow and take my jacket off to figure out how to put on my back protector.

It could be worse, I think as I loop the arm strap over my shoulder. It could be snowy and blowing up here. I feel someone behind me pulling the other strap up, and I turn around, expecting Jill.

It’s another competitor, who says through her mouthguard, “Here, let me help you.” OMG, these girls are nice? And shit, do I need a mouthguard?

Another girl, Abigail Harris, is wearing a rainbow-striped costume and a little helicopter hat. She’s singing to herself and doing a little dance. “I bought it specifically for this,” she says to us when we compliment her hat. “In fact, I bought two. You guys can have it if you want.”

“Does anyone need to use the ‘facili-trees’ before we commence to rip?” a guy with a clipboard and a walkie-talkie yells. The first girl is up, and the other competitors erupt in a chorus of hollers and praise. Is the dudes’ division so encouraging?

“Three… two… one… dropping!” the official says into his walkie-talkie. One after another the girls drop in, each getting the full treatment of cheers and high-fives.

Jill is up next, so I stop my relentless scab-picking long enough to shout some words of encouragement. I rub her arm a little, too. She’s focused, in the zone, and hops off the ledge with lanky confidence and drops out of sight.

The line she picked is impossible to make look good, owing to it being too narrow to turn in and too steep not to, and, like everything on this course, way scarier than it looks from below.

But if anyone could do it, it would be her. The crowd up top dwindles. I’m second to last, which seems to me to be cruel and unusual punishment. Maybe ageism. Yes, definitely ageism. I should have entered the master’s division. No, strike that. I should not have entered at all.

"I’m second to last, which seems to me to be cruel and unusual punishment. Maybe ageism. Yes, definitely ageism."

Finally, after what feels like an eternity in hell, I’m in the starting position. I look at the cornice and am suddenly unsure even if I remember how to ski. My stomach feels like a stormy sea.

I take a deep breath and remind myself that I’ve been sliding down snow for 41 years—twice as long as most of these girls have even been alive. I’m just going to ski my run, I say to myself with as much conviction as I can muster, and push off.

The motion instantly calms me, and I find my feet as I drop in. I remember how to do this. Relief and adrenaline flood my brain. I hop-turn the top, avoiding all the shrapnel, and then move into the gut and make smooth, fast arcs, my spray stinging my face as I go.

The snow is smoother and chalkier than it was yesterday, sanded down by all the edges. I’m not thinking about anything but my breathing now, and I open it up to go a little faster. Time stops, I don’t see anything except my next turn, and my rhythm is like a metronome. I know I’m skiing well.

Then I spot the hop at the bottom. I dog-leg over to the right to get on top of it, but, wait, there’s another set of trees with another hop underneath it. How did I not see this from below? Was I meaning to just do the lower one?

I am going to land in a tree. It’s too late now to abort, so I just point ’em and hop anyway. I land in the tree. My ski gets stuck, and I hip-check the ground, and then somehow right myself.

I’m still moving downhill, and the only way out is to ski a wide turn around it all, which would have required me to nearly stop completely. So I keep my speed and just point ’em again, straddling a crotch-high baby tree and skiing right over some others. I make it out and arc the two turns until the bottom, and I ski right into Jill’s arms.

“Oh my god you did it!” she yells. “I totally fucked it up!” I yell back, smiling so hard my lips get stuck on my dry teeth.

She has a beer for me, and I am panting and laughing so hard I can hardly sip it. I am finally able to ask her how her run went. “I have no idea if the judges could see it—” they couldn’t—“but I’m happy with it. I was breathing so hard I could taste blood,” she gushes.

I’m so proud of us I feel like I’m going to explode. Abigail, still in her costume, comes over and gives us a huge hug. “Nice turns, both of you!” she says. “Bummer about the tree,” she says, looking at me.

“Yeah, but I’m psyched I tried it,” I say, and realize that it’s true. We won’t know the results until tonight (Jill landed in the middle of the pack and I, owing to my little bushwhacking session, in the rear), and in this moment I feel a happiness I am not sure I have ever experienced. Like I’m floating over the snow.

We walk over and buy another beer so we can hang out and watch the boys, who are up next. I look around at the crowd, all cheering and drinking and relaxing in the sun.

"I am going to land in a tree. It’s too late now to abort, so I just point ’em and hop anyway. I land in the tree."

It could be the dopamine or endorphins or the second beer or the fact that my spleen is still happily intact and busy doing whatever spleens do, but suddenly it occurs to me how much this sport—these two wooden planks strapped to my feet—has brought me in my life.

A career, endless joy, laughter, terror, accomplishment, and, most importantly, friendship. I feel tears prick my eyes, because, even though I could probably afford that X-Box if I had chosen any other path, I wouldn’t trade this for anything. Even if it occasionally requires a back protector.

We settle in to watch the dudes’ runs, many of which end in carnage. They all huck bigger than the girls but perhaps ski worse. A few minutes in, Jill sits up straight and turns to me.

“Oh my god,” she says. “We have nothing else to be late for. What the hell are we going to do now?”

“Well, maybe we should start planning our next comp,” I say, unable to believe the words coming out of my mouth. “Lil’ Kims, round two.”

The squeal that comes out of her mouth would silence a troop of spider monkeys, and she puts her arms around me. “OK. But you gotta let me teach

you how to get air.”

“Deal.”

And there, somewhere between my liver and kidney, I feel a delicate tendril of fear sprouting again. Only this time, I kind of like it.

More SKI Adventure Stories

The Old Man and the Moguls

Alaska: Are You Good Enough?

This article—and many more like it—is available exclusively to Active Pass members, along with a host of others benefits such as access to the Warren Miller Entertainment film archive (that’s 50-some films), ski-instruction and fitness video tutorials, pro deals and members-only industry discounts, and a print subscription to SKI. Learn more about Active Pass or join here.