Peak Pursuits

As the ski world turns its attention this month to the 2001 World Alpine Ski Championships in St. Anton, Austria, we’ll see not only a race for titles but an experiment of sorts, a dry run for athletes hoping to peak for the 2002 Olympics. “Peaking” is a concept used throughout Olympic sports, and, not surprisingly, four years is a typical peaking cycle. When one Olympics ends, your training program for the next one begins. Most peaking programs try to simulate the big event one year out, so St. Anton is a perfect opportunity to see who is on the right track.

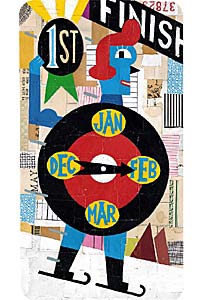

The basic concept of peaking is to create mini-training cycles of stress, fatigue and recovery. During each recovery period, your body enters a phase called “super compensation,” where it performs above its normal level. By starting a new training cycle just at the peak of the super-compensation phase, you can progressively raise your performance level. Timing is everything. Rest too long and performance will stagnate. Rest too little and you initiate a downward cycle of fatigue that leads to burnout or injury.

I was certainly aware of peaking while on the U.S. Ski Team, and I watched a lot of other teams do it quite well. For us, however, coaching regimes and philosophies changed so frequently that a four-year plan never came to fruition. Somehow every year we started off at a blistering pace, complete with strength routines during airport layovers and interval training on the first day in Europe. Inevitably, by mid-season we were fully fired and our dryland routine had devolved to volleyball in small European gyms. When Melinda Roalstad was hired by the ski team in 1991, I looked at her hyper-detailed daily training schedule with the same skepticism I had for every other “plan of the moment.” But her plan actually worked…the year after I left the team.

“Lillehammer in ’94 was where it all came together,” says Roalstad, who left the team in 1996 but has returned as medical director. “That’s where the science and the coaching gelled. I really believe it was a team effort.” The key factor was that the on-hill coaches were working with the off-hill dryland program, so the athletes were dealing with one overall load that made sense. Hilary Lindh didn’t grab the spotlight in ’94, but enlisted Roalstad to stick with her through the 1997 World Championships in Sierra Nevada, Spain. She recalls a feeling of total confidence while in the gate before her gold-medal run.

“Mentally I was right there,” Lindh says. “I had followed Melinda’s program religiously, and it made me feel strong, powerful and, maybe more importantly, in control of my destiny. Whether it worked because I believed it could, or because there’s really something to it is not something I can say for sure.” What is certain is that Lindh was so in tune with her body that she avoided the all too familiar scenario of training harder rather than smarter. Felix McGrath, the top U.S. slalom skier in the late Eighties and now alpine coach at the University of Vermont, looks back on his World Cup career as a case study in overtraining. “We had a good group of guys but we were always sick or injured because we never had a break,” says McGrath. “Everyone thought we were hurt because we didn’t train enough. But the truth was that we stuck to an archaic, rigid program that didn’t pay attention to the big picture of ski racing.”

As a college coach, McGrath’s bad experiences are at the core of his philosophy that racer management must be the top priority. “The whole NCAA season comes down to two days in March at the national championships,” he explains. “The only way to keep my guys healthy, motivated and fresh until then is to train just the right amount or less.”

Staying fresh is the biggest challenge skiers face. The travel, the time changes, the freezing and the schlepping all wear you down. As one athlete recalls, “I remember every year, training too hard in South America in August and praying we got rained ouut in Europe in the fall.” That happened often enough, but when the weather on the glaciers held, the athletes started biting the dust before the competition even started. One good indication that the philosophy has changed is that the U.S. Ski Team went into this year at an all-time low for injuries and with a full roster of healthy athletes. Andy Walshe joined the team as its new sports science director two years ago. When he started with the team, a major goal was figuring out how to prevent little injuries from becoming season-ending injuries. Part of that effort is improved monitoring methods, such as taking lactate levels during training and recovery to give athletes reference points. Perhaps more importantly, “We’re not trying to kill them out there,” says Walshe. “Alpine skiers don’t have a narrow-minded gym focus, and you wouldn’t want them to. That would take their spirit away.” An effective peaking program incorporates the individual preferences of the athlete.

Ironically, our country’s most successful alpine skier of all time is (philosophically, at least) an anti-peaker. Phil Mahre approached big events with studied nonchalance. “I just tried to treat Olympics and World Championships like an interruption to the World Cup season, nothing more.” His best advice for achieving peak performance is to know yourself. “You have to be smart enough to know what you need and strong enough to express that with conviction to your coaches.”

Indeed, one of Mahre’s biggest strengths was his ability to say no. “I often gave up the December races if I was struggling because there was no reason to be on top of my game then.” Even in a controlled sport such as swimming, peaking is difficult. You often see athletes who break records one week before or one week after the Olympics, but not on the big day. Add in the fact that skiing is an outdoor, high-altitude, equipment-intensive sport with variable course conditions, and you realize that even when you are peaking physically, there are no guarantees on the mental and technical side.

Mahre entered the ’82 World Championships as a favorite, having finished in the top three in every slalom and giant slalom race that season. He fell in both races, then won the very next World Cup race in France (his brother Steve, meanwhile, won the World Championship GS-just a few weeks after knee surgery).

McGrath fell in the ’88 Olympic slalom in Calgary and was second in the next World Cup race. “I peaked at the right time,” explains McGrath. “I just didn’t finish at the right time.”

Edie Thys missed a bronze medal in the ’88 Olympics by just .6 seconds. She can be reached at ethys@skimag.com or check out her previous Racer eX columns at www.skimag.com.